|

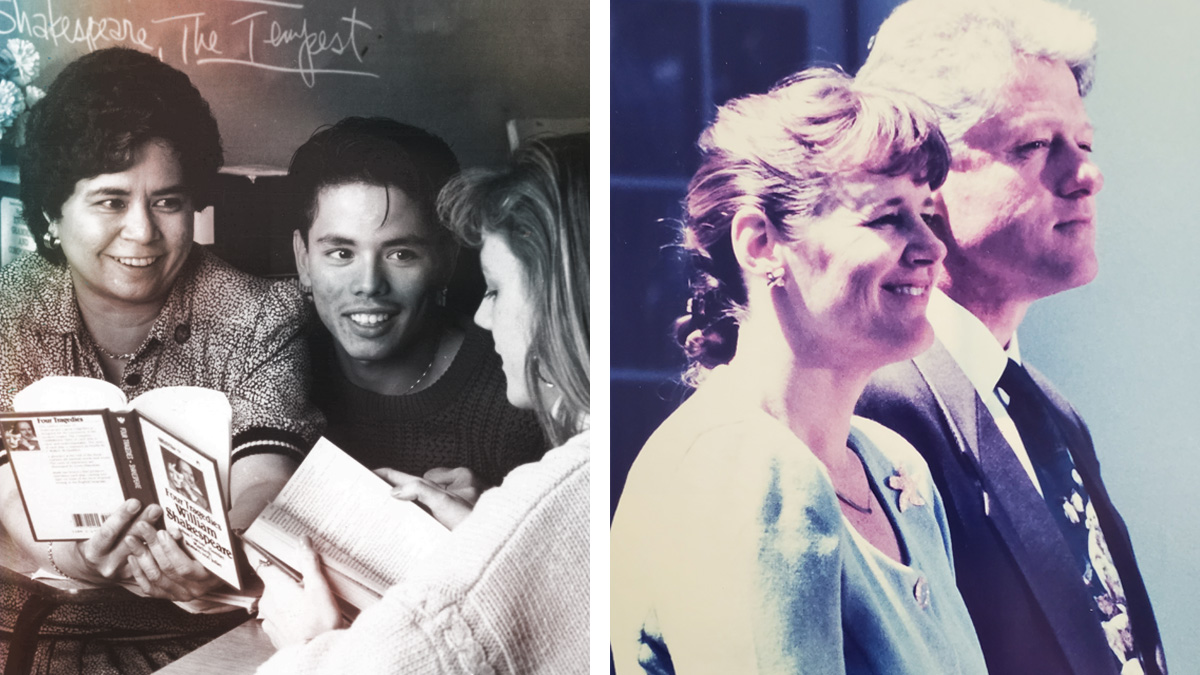

| Left: Gabay with students at Serra High. Right: McBrayer honored in the Rose Garden by President Clinton. |

Editor's Note: This story is part of SDSU NewsCenter's 125 Years of Excellence coverage.

In the early 1990s, the United States had about 2.5 million teachers. So when a San Diego State University graduate was singled out as National Teacher of the Year in 1990, it was an extraordinary accomplishment on its face.

Just four years later, it happened again.

The award, given every year since 1952, is the highest honor in teaching. Recipients get a Rose Garden ceremony with the president and spend a year traveling the world as an advocate for the profession. SDSU’s double claim to the honor was not only rare, but it was also bipartisan.

In 1990, Janis T. Gabay (’72, ’78) was honored by President George H. W. Bush.

In 1994, Sandra McBrayer (’86, ’89) received the award from President Bill Clinton.

For Gabay and McBrayer, being named National Teacher of the Year was a whirlwind experience that changed their lives. SDSU NewsCenter recently caught up with both to discuss the award, their careers since and how their experiences at SDSU and the College of Education prepared them for education immortality.

Dwelling in Possibility

As befits an English teacher of nearly five decades, Gabay’s professional journey can be summed up with her favorite quote by the poet Emily Dickinson: “I dwell in possibility.”

She always saw possibility in her students as a teacher at San Diego’s Junipero Serra High School and UC San Diego’s The Preuss School, where she chaired the English department and helped develop the staff after the charter for middle- and high-school students was founded in 1998.

“Each school year, each new school day and each new lesson meant I had the privilege and responsibility to create possibilities for my students and help them perhaps see new prospects for themselves,” said Gabay, who retired in 2021 after 48 years as an educator. “I truly believe that my classroom was a kind of sacred space and that the essence of what education is about lies in the classroom — between teacher and student and among students with their peers, guided by their teacher.”

Gabay grew up in a family with proud Hawaiian, Spanish, French and Filipino heritage. Her father served in the U.S. Navy for 30 years and her mother was a homemaker, and they achieved their American Dream by sending all five of their children to college.

The National Teacher of the Year honor, Gabay says, was a tribute to them.

“At the White House ceremony, it was a touching moment for me to see my parents, who took a long flight from Maui, Hawaii, to meet the President and First Lady of the United States,” she recalls.

Gabay used the opportunity to give voice to the concerns of educators while touring. While much of her planned international travel was cut short because of Operation Desert Storm, she spoke before national professional organizations in education, business groups, government agencies, universities and various cultural groups.

The conferences and speaking engagements didn’t stop until her retirement last year.

“For me personally, being named National Teacher of the Year was a privilege and responsibility,” Gabay said. “I wanted to represent the teaching profession with intelligence, integrity and honesty.”

Gabay credits her student teaching experience at SDSU for helping to prepare her well for the evolving challenges of the profession. At a time of social upheaval in the 1970s — as protests against the Vietnam War raged and the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements took center stage — she remembers professors who embraced the reality that education was in a state of change and worked to prepare teachers to succeed in diverse classrooms.

“I think my training and course work in the SDSU College of Education at that time was prescient,” Gabay said. “It gave me a stance of openness, excitement and — yes — a kind of fearlessness toward the ebb and flow of challenges and changes in my classroom to come, especially in my beginning years of teaching.”

An Advocate for Children

More than anything McBrayer remembers the grind of 300 days on the road. She spent much of 1994 visiting such places as Iceland, Germany and Japan, walking though too many airport terminals to count.

“People used to ask me where I was from,” McBrayer said, laughing. “I'd say ‘Delta Airlines,’”

But grueling as it was, the experience opened new doors. McBrayer had already made headlines in San Diego when, in 1987, she founded the Homeless Outreach School (now known as Monarch High School) — the first successful school for homeless and unattended youth. But being named National Teacher of the Year gave her additional reach and a desire to become a self-described “agitator.”

“I think it gave me a platform to be able to talk about underserved kids,” McBrayer recalls. “I used to have a very limited platform in San Diego, but (the award) allowed me to bring that to the White House, to the Department of Education and then internationally. Because those marginalized kids are everywhere. It put pressure on me to be fierce, to be driven. I carry that with me today.”

McBrayer is now Chief Executive Officer of The Children’s Initiative, an organization that works with government entities in California and across the nation to improve programs, policies and practices to better support children and families. A particular area of focus has been the juvenile justice system, where she has worked with U.S. Attorneys to move away from a punitive model towards prevention and early intervention.

In 2021, McBrayer and The Children’s Initiative took part in a multi-agency effort to support more than 1,300 unaccompanied migrant children fleeing Central American violence who were temporarily housed at the San Diego Convention Center. The Children’s Initiative worked to provide the children everything from underwear and toiletries to books and ice cream.

McBrayer remembers it as a hopeful experience.

“I remember seeing a dad reunited with his kid, and this girl is running at top speed across the Convention Center and leaps into his arms,” she said. “She's crying and he's crying — and she's safe.”

MacBrayer said her drive and tenacity to make a positive difference for vulnerable children was honed at SDSU — particularly in her master’s program. She fondly remembers being challenged by School of Teacher Education faculty members such as David Strom, Mernie Aste and Jesus Nieto.

“My master's was where the critical thinking really happened,” McBrayer recalls. “It's where professors would pose a question and we could challenge it. I was like, ‘Wait, I can disagree? It got me to where I started to think about what I believe in.”